User Tools

Sidebar

Table of Contents

UNIX/Linux Fundamentals course notes

For help with wiki syntax:

08/26/2014

First day of class today for Unix/Linux and the majority of the class was spent reviewing the syllabus online. We also received our logins to lab46 in the LAIR in the basement of Corning Community College's Business Development Center.

From within the LAIR, one logs in with:

ssh lab46and the website for the syllabus and course related material online is: http://www/haas/fall2014/unix

From an external machine from home, or when using WiFi in the LAIR on own laptop one logs in with:

ssh username@lab46.corning-cc.eduand the same website as above for syllabus, course info, etc. is located at: http://lab46.corning-cc.edu/haas/fall2014/unix

08/28/2014

Started this day with IRC session running from screen, a terminal multiplexer.

To start a screen session on lab46:

screenthen you can run any commands in here, like the example we did in class was:

whoThe method to detach is confusing if you aren't use to this procedure, but you hit Ctrl+a then release Ctrl+a and then hit d. Ctrl+a is a modifier key combination that tells screen that we are inputting command to it, tmux functions the same way but by default it's Ctrl+b is its modifier. To reattach to a detached screen session:

screen -r

To start irrssi, the IRC client program, run:

irssiOnce this starts up we can connect to the IRC server from lab46 with:

/server ircthen join channels as such:

/join #unix/join #lab46

Started to learn some basic commands:

ls - for “list” to show the contents of a directory, current directory if no arguments, or can be fed a path to show contents of that directory.

who - lists people currently logged into the system, lab46 in this case, by username, their psudoterminal, time they logged in, their time idle, process ID, and where they are logged in from.

man - man with any command given as an argument “man ls” or “man who” or even “man man” to access the online manual for commands. The man command shows the various options and usage for each command.

The Unix Philosphy

1) Small is beautiful

- In early days of computing machines had kilobytes of memory and our hello world program in C was 9 kilobytes alone.

2) Do one thing and do that one thing well.

- who should only need to show the pertinent data for its purpose and not try todo other things

- *COUGH* Emacs! *COUGH* “It's a great operating system, all it lacks is a decent text editor” Emacs by default has games, a calendar, a calculator, email, etc. etc. etc. Eight Megabytes And Constantly Swapping, Easily Maintained with the Assistance of Chemical Solutions, Easily Mangles, Aborts, Crashes and Stupifies, etc.

3)Everything is a file

- the keyboard is a file, the mouse is a file, the hard drive, etc

- run “cat /dev/psaux” and move your mouse.

3 Types of Files In UNIX

1) Regular/Ordinary files

- text, mp3, illegal torrent files

2) Directory (links)

- a directory is a file that links to other files

- metadata

3)Special Files

- keyboard, mouse, sockets, etc.

Access Control

3 tiers of ownership

- user

- group

- other(world)

“ls -l” the -l are options, arguments given to the command

each file given a set of permissions like “-rwx—r-x” 10 total bits, the first bit is occupied with a dash if its a regular file but could be d for a directory, l for a link, b,c,p,s for other special files

the first three bits after the first one belong to the user who owns the file, the next three belong to the user's group, and the last three are “other” or everyone else. these spaces can be occupied by r for read access, w for write access, or x for executable access, so each of the three bits for each group has its own rwx section, if any of these permissions are not there it is replaced with a dash. Each of these permissions has a numerical value associated with it as well:

4 for read

2 for write

1 for exec

0 for - or none

These can add up to any combination from 0 to 7 for each tier of ownership UGO, user, group, and other in that order.

With the “chmod” we can issue a blanket command defining the permissions for a file for all 3 tiers with using only 3 numbers, for example:

chmod 750 somefile.txtwould set the user(owner) of the file's permissions to 7 (4 for read + 2 for write + 1 for exec) then 5 for user's group (4 for read + 1 for exec but NO write priveleges) then others, everyone else, or the world to 0 meaning no read, no write or no execute privileges.

Author - Matthew Page

A quick injection of my notes from the first week, others can feel free to modify any part other than the Emacs reference

09/02/2014

New Class Notes System

Matt implemented a new system of showcasing notes. Each class three students will be chosen for the roles of author, designer, and reviewer. This is a great way of making an organized set of well rounded class notes. More information can be found here.

Alpine

We also checked out Alpine! This is the email client used to check our lab46 email accounts while logged into lab46. Learn more about alpine here.

Mercurial

The majority of our class time was spent setting up our mercurial repositories. Mercurial is a wonderful version control system that will allow us to back up our work, maintain multiple versions of a file/project, and much more! Documentation of this process pertaining to lab46 can be found here.

Home Directory

One last fact Matt left us with before class ended was how “~” is a representations of our home directory in Linux.

When logged into lab46 our default working directory is home.

Ex:

lab46:~$

Using the command pwd can help display this further.

lab46:~$ pwd /home/YOURUSERNAME lab46:~$

If we change directories from our home directory to src we can see this change!

lab46:~$ cd src lab46:~/src$

Authored by Thomas Arnold, designed and reviewed by Dan Shadeck. 09/09/2014

09/04/2014

Notes composed by vgarfiel:

Path Structure

- Unix root systems start with “/”. Also known as root directory and directory separator.

- Sub-directories of “/” include “home” and “mnt” which will include removable storage devices

- From “home”, the use is specified (i.e vgarfiel)

- Upon entering lab46, typing “pwd” shows you in which directory you're located

- Relative paths: used when working with your own directories

- Changing from your home directory to “src” using the command “cd src”

- Absolute paths: used when working with public directories, universally specific

- From main directory, the relative path to reach bin would be cd bin

- From any directory on system, absolute path to reach bin would be cd /bin

Commands

- “echo” displays the messages —- ex. “echo “Hello”“

- “cat” displays what is within the file, without a given specific file it assumes STDOUT

- “ctrl c” quits job

- “tail” views end of file by default

- “tail -f” will prevent the close of the program

- “tty” shows you which session belongs to you —- ex. When playing N64, this would relate to which controller/character belongs

I/O Stream

I/O Stream Redirection

- ”>” redirects STDOUT to file (writes)

- “»” redirects STDOUT to file (appends)

- “2>” redirects STDERR to file (writes)

- “2»” redirects STDERR to file (appends)

- “<” redirects STDIN from file

System Files

- bin-stores basic commands to manipulate file

- sbin-meant for system administrators

- boot-contains files necessary for computers to start up

- dev-has special files(not regular or directory) *could pertain to hardrive*

Note: Within unix there is no user “un”delete, therefore when a file is deleted it is put on system extra space which can easily be thrown away when someone uses that space. Beware!

Reviewer: mquesad1

09/09/2014

Status

First, I would like to remind everybody of this useful command that is now available to us.

lab46:~$ status unix

this will display your progress on attendance, opus, and projects.

Cal

Next, we learned some interesting UNIX commands today.

lab46:~$ cal

This command has several arguments you can find some interesting things out with the day and the year. There is also another command

lab46:~$ ncal (year) -e

This tells you the date of Easter on the given year.

Date

Another command is

lab46:~$ date

This tells you the date. This command has several powerful arguments.

Pom

My personal favorite command we did was

lab46:~$ pom

This stands for phase of moon. It tells you the current state the moon in percentage.

Write

Finally, we learned a command to message other users. Cast a who to see whose on then do the following command.

lab46:~$ write (user)

This will allow you to send a message to the user.

- You do not type your message until after you do the command.

Man

For more information on any commands, get to your shell and man them, man!

lab46:~$ man (optional page number) command

/

We also went through the / directories to get a feeling of what goes where. There is a proc folder in / and it has all the current processes running manifested into directories. It also has cpu information. If your curious on what a t flag at the end of file permissions does, it prevents deletion. The var folder in / has a variety of stuff in this is also a log info.

/usr

The /usr/include folder has header files. The /usr/lib has more library's that applications use. The /usr/local has local modification. The /usr/sbin has secondary tools for the administrator, has daemons a.k.a. servers and manipulation tools. Look under /usr/share if you want to learn about some installed software. /usr/src is where some people put source code that runs on the system.

Author: Derek Southard

Designer: Dan Shadeck

Reviewer: Matthew Page

09/11/2014

VI

Vi's inception

Bill Joy(Computer Scientist) had an idea for visually inserting text and inputting commands into the command line via text editor.

ex and ed were earlier forms of unix command line text editors before Vi was created.

Vi iMproved

Vi is a useful and powerful text editor. If used properly, It can dramatically speed up otherwise redundant typing processes. Falling back on our class themes of,

“Manipulation being the biggest part of the entire unix experience”

“Being lazy in a productive fashion”

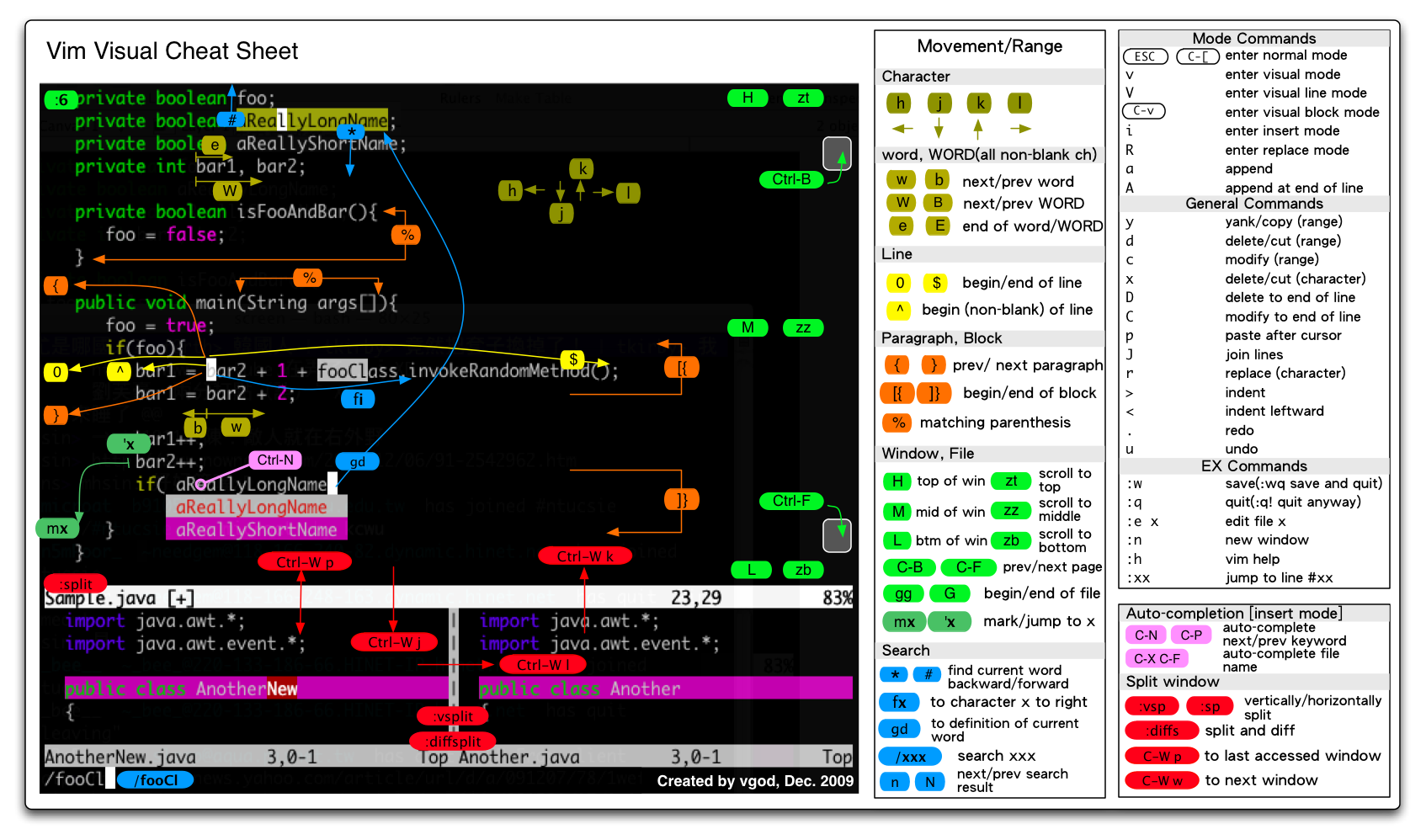

Vi Cheat Sheet

Check this link out for additional help. http://benmccormick.org/tag/learning-vim-in-2014/

Also, if you issue “vimtutor” on the command line you will be launched into a built in Vi tutorial.

Note Taker Roles:

- Author: Aaron Carson

- Designer: Tyler Mosgrove

09/16/2014

The best class you will ever take issue number 7 It's all about the Vi

Copying lines

:.co$ = copy the current line to the last line, the . selects the current line and $ the last line :2,4co9 = copy lines 2 through 4 to line 9

Moving lines

:3m7 = moves line 3 to 7 :.,+4m16 = moves current line and next 4 lines to line 16

Other commands

:r filename = read :w filename = write :q = quit :q! save and quit

Regular Expressions

Regular Expressions are patterns the computer can find, and will be covered in further depth at a later class.

:%s/[a-z]$/Z/g = This finds any line ending in a lowercase letter and replaces the letter with Z :%s/./DEADBABY/g = Replaces every character with DEADBABY, That's a lot of deadbabys

Using Vi to setup preferences

:set number = sets line numbering :set tabstop=3 = sets tab spacing to 3 :set shiftwidth=3 = sets shift width to 3

Go forth and enjoy the wonder of Vi

09/18/2014

Submit tool - New feature

First, we were given the command:

submit unixwhich allows us to check our submitted material to ensure that we submitted assignments. One can re-submit assignments to update them.

lab46:~$ submit unix unix projects: puzzlebox, submitted on 20140918-133831 resume, submitted on 20140901-220455 intro, submitted on 20140831-132213 archives, submitted on 20140906-171904 lab46:~$

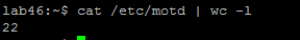

cat

Next, our class went on to discuss text processing starting with the command cat. The class used this command on the Lab46 message of the day (/etc/motd).

cat /etc/motd

Next, Matt showed us the cat command's '-n' argument which gave us numbered lines on the /etc/motd and the '-e' argument which recognized the end of the lines of /etc/motd with $(end of line).

cat -e /etc/motd

Then, we discussed ASCII and whitespaces, which are characters that are not visualized such as backspace or transmit off(XOFF, ctrl+s) and transmit on(XON, ctrl+q). The importance of this is if one uses certain commands it could result in these whitespaces to try and be implemented therefore we learned some other commands.

od

The od command allowed us to view /etc/motd in octal,

od /etc/motdand od -x allowed us to view /etc/motd in hexadecimal.

od -x /etc/motd

Endianness

When we converted a small section of the hexadecimal info, our class noted that the sequential ordering of bytes was flipped every two bytes.

Where we might have expected the string “ABCD” to result in 41 42 43 44 0a 00 (newline followed by end of file/NULL terminator character), instead we have:

lab46:~$ echo "abcd" > ascii lab46:~$ od -x ascii 0000000 4241 4443 000a 0000005 lab46:~$

When the lower order byte (the smaller, or little-end) is presented first, the CPU is referred to as little endian.

When it is presented in the way we expect to read numbers (from left to right, higher order byte first (i.e. the big end)), we call that big endian.

- Big Endian is typically used in:

- network communications (i.e. Network Byte Order)

- and some CPUs (just a partial list):

- SPARC

- PowerPC

- some ARM processors

- some MIPS processors

- Little Endian is the native ordering of Intel compatible CPUs, and is also used by many ARM processors.

grep

Finally, the class discussed grep and the pipe command; grep or global regular expression print is used to grab certain patterns from a file. In class we used this to grab 'the' from /etc/motd.

grep '\<the\>' /etc/motd

pipes

Next we discussed the | (pipe) command and noted that this command can be used to combine commands where we take the output from the first command and use it for the input of the second command. We used the pipe command with both commands od -x and grep: od -x etc/motd | grep '41' This was used to find all the lines that had the hex pattern 41 in it.

od -x /etc/motd | grep '0a' | wc -l

Note Taker Roles:

- Author: mquesad1

- Designer: Matthew Page - Added DocuWiki Syntax and corrected the reversed XON and XOFF keyboard shortcuts. Threw in a couple commands.

- Reviewer:

09/23/2014

The best class you will ever take!

The Unix Pipe |

- This is a great little tool that sends the output from the function on the left as input to the function on the right.

Heads or Tails?

- The head command displays the first (n) lines of output

- The tail command displays the last (n) lines of output

- The -n modifier can be used to change the number of lines.

- ex. cat who.dat | wc -l In this example there were 57 lines displayed

if we wanted to break this up into three equal sections we might end up with something like this

cat who.dat | wc -l | head -n19 cat who.dat | wc -l | head -n38 | tail -n19 cat who.dat | wc -l | tail -n19

Sort it all out

- The sort command does just that, it sorts lines of text files putting them in order

Crunching some numbers

- The bc command will bring up the calculator

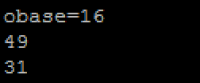

- If you need to switch to Hex it's not a problem just type obase=16

- Ctrl D will get you out to the prompt

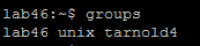

Do you belong to any groups?

Note Takers

- Author = Nick Vitulli

- Designer = Thomas Arnold

- Reviewer = Julian Cliteur

09/25/2014

In today's class, we learned about:

- The newly discovered bug in the Bash shell

- Fork bombs

- The importance of quotes

- Creating a specific variable

- Various commands

- Dinosaurs with hats

Bash Shellshock Bug

The Shellshock bug is a recently discovered vulnerability in the Bash shell. This vulnerability basically allows anyone with the proper knowledge access to your device that runs on the bash shell. This is an extremely vague explanation, as there is a lot to discuss on the topic. So if you are interested, read further here, or even further here.

Fork Bombs

Fork bombs are a type of DoS (Denial of Service) attack. This was unknowingly brought upon Lab46 the previous day. Fork bombs create process trees that continually expand (fork) until there are no more available system processes. This effectively blocks another user from opening any type of process in a bash shell prompt. More information can be found out here.

The Importance of Quotes in Unix

- ' = full quote. This is taken as a literal quote.

- “ = half quote. The half quote is used for expanding variables.

- ` = back quote. Otherwise known as a backtick, is used when you are expanding a command.

- ( ) = `. Parentheses are the same as a backtick. They are technically interchangeable. However, the backtick is cooler.

How to Create a Specific Variable

Sometimes in unix, it may be useful to create a specific variable to use if you find yourself doing something repetitively. To solve this problem, you would create a specific variable.

To create a specific variable:

- variable = $(command)

- example: Users Online: uol=$(/usr/bin/who|wc -l)

- echo “there are $uol users on the system”

Other Commands Learned

- ps: stands for process status; this command shows the currently running processes. More info here.

- bash: opens another instance of bash, which is the shell that you are currently working in.

- cut: cuts out and shows region of information. For example: the command getent passwd|cut -d ':'. This will cut based on the character position.

Dinosaurs with Hats

Learn the wonderful secret of dinosaurs with hats:

- Go to: vogue.co.uk

- Once page is loaded, type the Konami code

- Press A to your hearts delight and be amazed

Author:

Designer:

Reviewer: Andrew Hoover

09/30/2014

Today we went over important commands we introduced the data proc assignment and went over useful commands we will want to use for it.

- WC - short for word count

- Head - output the first part of a file

- Tail - output the last part of file

- Grep - searches input files for lines containing a match

- Cut - remove selected fields

- Sort - for sorting lines

- Cat - concatenate files and print to stdout

- Uniq - report or omit repeated lines

- Pipe or | - send stdout of one program to stdin of another

- Tr - translate, squeeze, and delete

And we also went over “Sed” and “Print F” commands

Then we learned that there are different sections of the Man Page

Then we went over Wildcards

”?“ matches any single character example: ls ???? will find all 4 character words in the list and list them.

“*” will match 0 or more of any character

”[]“ will match any one of the enclosed characters

”[^]“ will not match any of the enclosed characters

“\” is an escape character.

Specific examples we went over in class were:

- ls ?[^aeiou]?

- ls c[aeiou]*t

- ls ????

- ls l*

- ls *.zip

- ls *.tar*

and we were introduced to the command “apropos”

- Author: Samantha Smith

- Reviewer: Dylan Dewert

10/02/2014

Practicing commands today with wildcards. Went into usr/bin to count files :D

Wildcards:

| Wildcard Char | Meaning |

|---|---|

| ? | matches any single character |

| * | match 0 or more of any character |

| [] | match any one of enclosed characters |

| [^] | do not match any of enclosed chars |

Shows the number of files with 5 or more characters in the name:

lab46:/usr/bin$ ls -d ?????* | wc -l 678

shows the number of files that have at least 4 or more characters, and whose first, second, and last character is oneof the jeopardy characters.

lab46:/usr/bin$ ls -d [rstlne][rstlne]?*[rstlne] | wc -l 43

All files whos names do not have vowels in them.

lab46:/usr/bin$ ls -d [^aeiouy][^aeiouy][^aeiouy] | wc -l 27

Looking for the number of all directories and symbolic links

lab46:/usr/bin$ ls -l|egrep '^(l|d)' | wc -l 203

- Author: Casper Clay

- Designer: Derek Southard

10/07/2014

Started out class talking about the dataproc assignment. Due date changing to the 22nd; however, if we want a bonus point, we can still turn it in by the original due date.

A process is a “program in action.”

Each process has a PID or ProcessID.

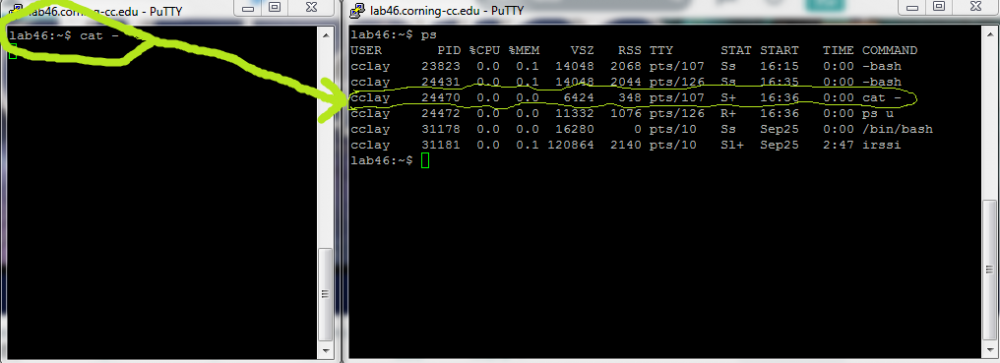

Running the command ps lists the current processes running and their PID's, as-well as other information regarding each process running.

In this example, we can see that when we run the command cat and let it sit, it can then be viewed by running the process ps in a different terminal.

We can kill processes with the kill command. Here are the different kill signals available.

lab46:~$ kill -l 1) SIGHUP 2) SIGINT 3) SIGQUIT 4) SIGILL 5) SIGTRAP 6) SIGABRT 7) SIGBUS 8) SIGFPE 9) SIGKILL 10) SIGUSR1 11) SIGSEGV 12) SIGUSR2 13) SIGPIPE 14) SIGALRM 15) SIGTERM 16) SIGSTKFLT 17) SIGCHLD 18) SIGCONT 19) SIGSTOP 20) SIGTSTP 21) SIGTTIN 22) SIGTTOU 23) SIGURG 24) SIGXCPU 25) SIGXFSZ 26) SIGVTALRM 27) SIGPROF 28) SIGWINCH 29) SIGIO 30) SIGPWR 31) SIGSYS 34) SIGRTMIN 35) SIGRTMIN+1 36) SIGRTMIN+2 37) SIGRTMIN+3 38) SIGRTMIN+4 39) SIGRTMIN+5 40) SIGRTMIN+6 41) SIGRTMIN+7 42) SIGRTMIN+8 43) SIGRTMIN+9 44) SIGRTMIN+10 45) SIGRTMIN+11 46) SIGRTMIN+12 47) SIGRTMIN+13 48) SIGRTMIN+14 49) SIGRTMIN+15 50) SIGRTMAX-14 51) SIGRTMAX-13 52) SIGRTMAX-12 53) SIGRTMAX-11 54) SIGRTMAX-10 55) SIGRTMAX-9 56) SIGRTMAX-8 57) SIGRTMAX-7 58) SIGRTMAX-6 59) SIGRTMAX-5 60) SIGRTMAX-4 61) SIGRTMAX-3 62) SIGRTMAX-2 63) SIGRTMAX-1 64) SIGRTMAX

The following can be used to close the process cat with the appropriate PID:

USER PID %CPU %MEM VSZ RSS TTY STAT START TIME COMMAND cclay 24925 0.0 0.1 14048 2048 pts/10 Ss 16:46 0:00 -bash cclay 24933 0.4 0.1 14048 2044 pts/107 Ss 16:46 0:00 -bash cclay 24941 1.0 0.0 6424 348 pts/10 S+ 16:46 0:00 cat - cclay 24942 0.0 0.0 11332 1076 pts/107 R+ 16:46 0:00 ps u lab46:~$ kill -1 24941 lab46:~$ kill -HUP 24941 lab46:~$ kill -SIGHUP 24941

If we kill a process by simply saying “kill PID”, the kill process automatically uses signal “15” or “SIGTERM”

In the kill command, signal “9” or “SIGKILL” is the most powerful signal and will close anything. It should be used sparingly, as it can cause problems if not fully understood.

Running “ps aux”, we can view every process running on the system.

Here is an example of viewing all of a single persons processes on the system.

lab46:~$ ps aux | grep $USER root 24922 0.0 0.2 99900 4520 ? Ss 16:46 0:00 sshd: cclay [priv] cclay 24924 0.0 0.1 99900 2152 ? S 16:46 0:00 sshd: cclay@pts/10 cclay 24925 0.0 0.1 14056 2068 pts/10 Ss 16:46 0:00 -bash root 24930 0.0 0.2 99900 4524 ? Ss 16:46 0:00 sshd: cclay [priv] cclay 24932 0.0 0.1 99900 2152 ? S 16:46 0:00 sshd: cclay@pts/107 cclay 24933 0.0 0.1 14056 2096 pts/107 Ss 16:46 0:00 -bash cclay 24953 0.0 0.0 6424 344 pts/10 S+ 16:47 0:00 cat - cclay 26488 0.0 0.0 11332 1064 pts/107 R+ 16:57 0:00 ps u aux cclay 26489 0.0 0.0 15228 948 pts/107 S+ 16:57 0:00 grep cclay lab46:~$

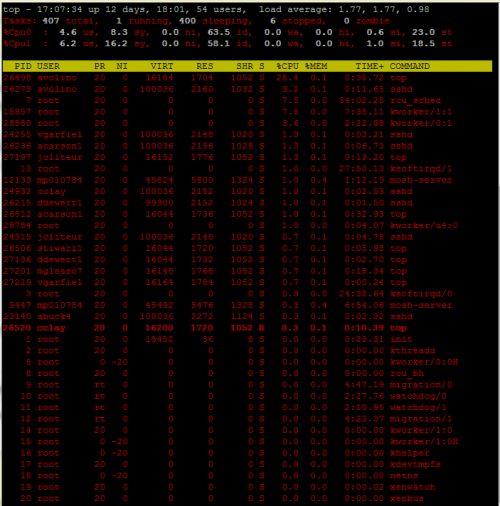

Another interesting command is top, which will show realtime system information such as process and resource usage.

Example(Only the first 12 lines of output):

top - 16:58:09 up 12 days, 17:52, 49 users, load average: 1.39, 0.57, 0.33 Tasks: 408 total, 4 running, 399 sleeping, 5 stopped, 0 zombie %Cpu(s): 2.1 us, 7.9 sy, 0.0 ni, 75.6 id, 0.0 wa, 0.0 hi, 0.3 si, 14.1 st KiB Mem: 1535680 total, 1499612 used, 36068 free, 398056 buffers KiB Swap: 131068 total, 37104 used, 93964 free. 524684 cached Mem PID USER PR NI VIRT RES SHR S %CPU %MEM TIME+ COMMAND 31518 thakes3 20 0 120988 2484 1364 S 23.3 0.2 3:07.53 irssi 28580 root 20 0 0 0 0 S 4.3 0.0 2:08.08 kworker/0:1 7 root 20 0 0 0 0 R 3.6 0.0 33:35.86 rcu_sched 26493 jjacobs7 20 0 16044 1700 1052 S 2.6 0.1 0:00.52 top 26549 wedge 20 0 9908 1740 1348 S 2.3 0.1 0:00.07 bash

You can customize the top process by toggling keys such as “z” for color, or 1 for specific cpu core usage.

In unix we use shells. The default shell that we use is Bash.

(View the latest bash vulnerability here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shellshock_(software_bug)

AT&T UNIX VS. BSD UNIX SHELLS

| Shells | Meaning |

|---|---|

| AT&T- sh | bourne shell |

| AT&T- bash | bourne again shell |

| BSD- csh | C shell |

When running a process in a terminal, we can save it rather than killing it by using CTRL Z

Example:

lab46:~$ cat - ^Z [1]+ Stopped cat - lab46:~$

We can view these stopped or active process with the command jobs. We can use the command bg to run processes in the background and the command fg to run processes in the foreground.

Example of freezing, viewing, and re-running processes:

lab46:~$ sleep 3600 (sleep 180;echo hi) ^Z [2]+ Stopped sleep 3600 lab46:~$ jobs [1]- Stopped cat - [2]+ Stopped sleep 3600 lab46:~$ bg 1 [1]- cat - & lab46:~$ jobs [1]+ Stopped cat - [2]- Stopped sleep 3600 lab46:~$ bg 2 [2]- sleep 3600 & lab46:~$ jobs [1]+ Stopped cat - [2]- Running sleep 3600 & lab46:~$ fg 2 sleep 3600

Author: Matthew Page

Designer: Samantha Smith

Co-Author: Casper Clay

Reveiwer: Derek Southard: Good job guys, it's hard to find room to improve.

10/09/2014

We can view hidden files by issuing ls -a , which will show all files. Lots of these hidden files, such as .bashrc , are configuration files.

A useful command we can use is alias. Here is an example so that when we type bob, we get bob printed on our terminal.

lab46:~$ alias bob='echo bob' lab46:~$ bob bob

An alias will stay until you end your session. You can take aliases away with the unalias command. If you want permanent aliases, you can add them in .bashrc in our home directory (hidden config file).

The environment variable $PATH shows all of the paths that the system will look for commands. If we type jim, it will look for a command called jim in all of the following places:

lab46:~$ $PATH -bash: /usr/local/bin:/usr/bin:/bin:/usr/local/games:/usr/games: No such file or directory

Lets begin our first look into scripting!

Shell Scripts

We can save shell scripts in files ending in .sh or .bash Here is an example of a simple script called myscript.sh 3 line script:

df who ls

Now lets run this script (not all output included)!

lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$ bash myscript.sh Filesystem 1K-blocks Used Available Use% Mounted on /dev/xvda1 3997376 1784952 1986328 48% / udev 10240 0 10240 0% /dev tmpfs 153568 160 153408 1% /run

We are not able to run this script with ./ because we don't have the proper permissions to execute it, which is why we used bash. If we changed the permissions with chmod, we will be able to then execute the script normally. Example (not all output included):

lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$ chmod 700 myscript.sh lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$ ./myscript.sh Filesystem 1K-blocks Used Available Use% Mounted on /dev/xvda1 3997376 1784968 1986312 48% / udev 10240 0 10240 0% /dev tmpfs 153568 160 153408 1% /run

To see our environment, which is bash: #!/bin/bash

Now lets make another cool script called nametest.sh to create a mini program that asks for your name and spits it back out :D Here is the script:

echo -n "What is your name? " read name echo "Hello, $name, nice to meet you! " exit 0

Now lets run it!

lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$ ./nametest.sh What is your name? Casper Hello, Casper, nice to meet you! lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$

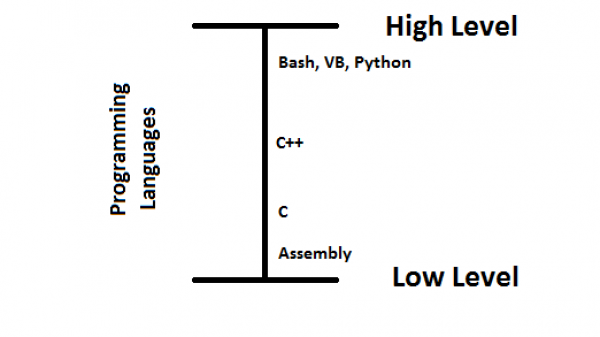

Bash is a higher level among programming languages. We don't have to worry about things such as data types.

We can use tab completion, AKA push tab after typing in an in-complete name, to complete unique names, such as file names, without typing it all out. If we have two files with similar names, tab completion will complete the name up until the point at which it is still unique. If you have two files with similar names such as hhhhhs and hhhs, you can push tab two times to get information on the files and see why it wont complete the entire name. Example:

lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$ ls hasdkhfakjhfafqhfiufubflks hasdkhfakjhfafqhfiufubflksajfasjfdsafjffaoiehfiquhfahf myscript.sh nametest.sh lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$ hash hasdkhfakjhfafqhfiufubflks/ hasdkhfakjhfafqhfiufubflksajfasjfdsafjffaoiehfiquhfahf/ myscript.sh nametest.sh lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$ hash

We can use the rm command to remove files and directories. Using rm -f deletes a director and everything in it.

Now lets test checking conditions inside our scripts and using loops. It is important to remember that things must be properly spaced such as 5 = 0. If it was 5=0, the script will try to assign 5 to 0 instead of checking the condition.

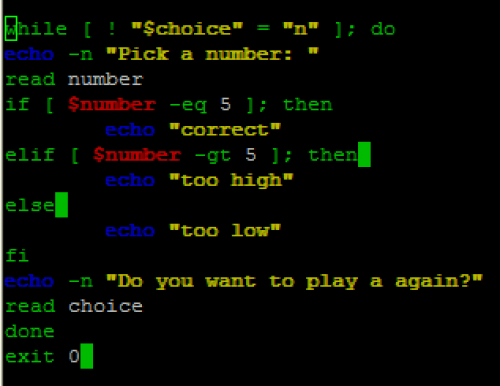

Here is a script called numbertest.sh (we used -eq for = and -gt for > to avoid string vs number comparison problems):

Now lets run this amazing game we just made!

lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$ ./numbertest.sh Pick a number: 1 too low Do you want to play a again?y Pick a number: 7 too high Do you want to play a again?y Pick a number: 5 correct Do you want to play a again?n lab46:~/src/unix_linux/classwork/10_9_14$

Co-Author: Casper Clay

Reviewer: Sudesh Tiwari: Good job!

10/21/2014

First day back from a week long break!

Summary

We picked up today where we had left off the previous thursday, talking about scripting. Math concepts, specifically the modulus, were discussed in relation to writing code.

The Modulus

The modulus has several different meanings, but for our purposes, it is a by-product of division. Otherwise known as the remainder. It is represented by %. The modulus will also never be greater than the divisor minus one. For a more in-depth definition, checkhere.

Why is this number significant?

The modulus is important to us for many reasons. It can be used to:

- keep a loop function within a certain range

- finding odd and even numbers

- clock arithmetic

Example:

int a[10]; for (int i = 0; true; i = (i + 1) % 10) { // ... use a[i] ... }

Here we see the modulus used to keep i in a specified range of 0-10.

Playing around on the command line

Using the RANDOM function, we can test out the use of the modulus.

lab46:~$ echo$((RANDOM%100)) 45 lab46:~$ echo$(((RANDOM%100)+1)) 100 lab46:~$

Using a modulus of 100, it ensures that the random number returned is between 0 and 99. Adding 1 to that changes that range from 0-99 to 0-100. So, using this idea, we expanded our scripting knowledge by creating the best game ever.

Here is the above example incorporated into a classic guessing game.

#!/bin/bash choice=$((($RANDOM%100)+1)) guess=0 while [ "$guess" -lt 6 ];do echo -n "Guess a number: " read number if [ "$number" -eq "$choice" ];then echo "Sweet moustache! You're correct!" exit 0 elif [ "$number" -lt "$choice" ];then echo "Higher" else echo "Lower" fi let guess=$guess+1 done echo "The correct number was: $choice" echo "Better luck next time!" ~ ~ ~ ~ ~ "Scriptgame.sh" 18L, 376C 1,1 All

Using the modulus function, we make the random number pool more manageable, so that the game isn't logically impossible.

To run and experience the magic of the best game ever:

lab46:~$ bash filename.sh

Author: Andrew Hoover Designer: Reviewer:

10/23/2014

Today we did some more scripting. We wrote a script in class to take data from a file and tell us which parts of the data were even numbers.

#!/bin/bash total=0 evens=0 for number in `cat data.dd`;do evenchk=`echo "$number%2"|bc` if [ "$evenchk" -eq 0 ]; then let evens=$evens+1 fi let total=$total+1 done echo "out of $total numbers, there are $evens even numbers" exit 0

The remander of class was spent working on our next project, which is to take our current grades from lab46:~$status unix and process it so that we can get an actual grade from the data.

Take stauts output -Calculate project -Calculate opus -Calculate attendance Then take the % of those to their actual percentage value Project 36% Opus 36% Attendance 28% Calc current grade Display stuff/Useful information

We also talked about Binary Calculator again “bc in cli”

You can use bc directly in your command line and it runs as a calculator. You may also use it with pipe, for example:

echo 4+4 | bc 8

November 4, 2014

Today we venture off into regular expressions!

*Remember - Wildcards are for files, regular expressions are for text *

Regular Expressions are used to describe patters, patterns in text that we are looking for.

| Regular Expressions | Meaning | Extended Expressions (newer)? |

|---|---|---|

| . | matches any single character | No |

| * | match 0 or more of the previous | No |

| [] | match any one of enclosed characters | No |

| [^] | do not match any of enclosed chars | No |

| \< | match start of word | No |

| \> | match end of word | No |

| ^ | match start of line | No |

| $ | match end of line | No |

| | | or | Yes |

| () | grouping → \( \) (sed) | Yes |

| + | match 1 or more of the previous | Yes |

Now, lets try some stuff out.

To find the number of words that are exactly 4 characters long, the following can be done:

lab46:/usr/share/dict$ cat words | grep '^....$' | wc 3346 3346 16730

Therefore, there are 3346 words that are exactly 4 letters long.

To find the amount of words that are at least 4 letters long and end with a lower case g, the following can be used:

lab46:/usr/share/dict$ cat words | grep '...g$' | wc 6999 6999 70411

This results in 6999 words.

You can also use this command to do the same thing. The reason the previous command worked was because the beginning of the line did not matter.

lab46:/usr/share/dict$ cat words | grep '^....*g$' | wc 6999 6999 70411

This also results in 6999 words.

We can find the words with at-least 3 characters and are all lowercase with the following:

lab46:/usr/share/dict$ cat words | grep '^[a-z][a-z][a-z][a-z]*$' | wc 62797 62797 584774

We get back 62797 words.

To find any words that have at least 3 or more vowels, we can use the following:

lab46:/usr/share/dict$ cat words | grep '^.*[aeiouy].*[aeiouy].*[aeiouy].*[aeiouy]*' | wc 64422 64422 682102

This results in 64422 words.

We can enable extended regular expressions mode by using **egrep** instead of **grep**. **fgrep** is used to find only literal strings. This can be faster if you are trying to only find literal strings.

To find any words that end in 'ed' or 'ing', we can use the following:

lab46:/usr/share/dict$ cat words | egrep '*(ed)$|(ing)$' | wc 13412 13412 130200

This results in 13412 words.

Next class, we will blow our minds once again by learning about sed :D

Author: Casper Clay

11-06-2014

Entry for week 2 opus[1]»

status unix|grep 'opus'|sed 's/^.*\([01]\):\([a-z][a-z]*\):\(week\)\([0-9]\)\(.*\)$/\5 for \3 \4 \2 [\1]/g'

For matching usernames starting with any of our initials.

getent passwd|grep '^[bst]' | sed 's/^\([a-z][a-z0-9]*\):x:\([0-9][0-9]*\):[0-9][0-9]*:\([A-Z][ .A-Za-z0-9]*\):\/home.*$/\3 is users \1 with userid \2 /g'

Author:

Sudesh Tiwari

November 11, 2014 Notes

Author: Victoria Garfield - vgarfiel

Find the location of a file using the command “whereis”

lab46:~$ whereis status status: /usr/local/bin/status /usr/local/bin/status.logic

FIND OUT WHEN THAT SHIT WAS CREATED

lab46:~$ status unix > output lab46:~$ stat output File: ‘output’ Size: 1925 Blocks: 8 IO Block: 1048576 regular file Device: 15h/21d Inode: 130943001 Links: 1 Access: (0644/-rw-r--r--) Uid: ( 5933/vgarfiel) Gid: ( 5000/ lab46) Access: 2014-11-11 17:04:51.166171228 -0500 Modify: 2014-11-11 17:04:54.330231551 -0500 Change: 2014-11-11 17:04:54.330231551 -0500 Birth: - lab46:~$ stat output | grep "Modify" Modify: 2014-11-11 17:04:54.330231551 -0500

MAKE THAT SHIT PRETTY

lab46:~$ stat output | grep "Modify" | cut -d : -f2 | date Tue Nov 11 17:09:12 EST 2014

SHOW HOW LONG AGO FROM THE BEGINNING OF TIME THE FILE WAS CREATED

lab46:~$ date -d "$(stat output | grep 'Modify' | sed 's/^Modify: //g')" +%s 1415743494

CREATE VARIABLES FOR SHORTCUTS

lab46:~$ ftime=`date -d "$(stat output | grep 'Modify' | sed 's/^Modify: //g')" +%s` lab46:~$ echo $ftime 1415743494

November 13, 2014

at commands

at - executes command at specified time

atrm - deletes job by job number

at 16:16 - sets command at 4:16 Linux time

ls > out - command that will run at 4:16

atq - shows the list of commands that you set to run

crontab -e - lets you choose an editor to create a repeating command

*/4 * * * * /usr/bin/who - runs that command every 4 minutes of every hour, day, week, month

After a successful crontab command it should say: crontab: installing new crontab

last - shows when a user logged in

last | grep $USER | wc -l - shows how many times you logged in

last | grep $USER| grep Oct | wc -l - shows how many times you logged in October

Author: Jcliteur