Table of Contents

Corning Community College

CSCS2330 Discrete Structures

~~TOC~~

Project: Binary Data Tool (bdt0)

Objective

To apply our binary data knowledge and interactions in the creation of a useful tool for aiding us in the debugging of our dcfX endeavors.

Background

We've had a newfound exposure to data this semester, and how programming languages like C interpret different forms of data; we look at things like data type and corresponding storage allocated, and we use these as ingredients in our programmatic solutions.

Yet- we've also seen how that inserted layer of abstraction between us and the computer has provided an opportunity to omit and later properly learn what is actually going on: it isn't just about integers and floating point values and ASCII characters… and while each has its own unique ways of accessing and manipulating, they actually do share a common underlying foundation.

As the computer and all data is largely the same, it is important we increasingly see it as just sequences of 1s and 0s, accessed in units of bytes.

Binary data merely refers to data as the computer stores it. The computer is a binary device, so its raw data (as it exists on various forms of storage and media) is often referred to as binary data, to reflect the 1s and 0s being represented.

Task

Your task is to write a hex viewer, along the lines of the xxd(1) tool found on the system. We have made use of xxd(1) rather extensively to help us in identify encoding deviations with our dcfX implementations against proper specification-generated output.

An insightful exploration is, while we've been utilizing this tool to aid us in our debugging, there is some important concepts to be gleaned by exploring the implementation of such a tool, which is what this project is about.

Grabit

I have prepared some files to assist in our endeavors, which can be obtained through the use of the special grabit tool found on lab46:

lab46:~/src/discrete$ grabit discrete bdt0 make: Entering directory '/var/public/SEMESTER/discrete/bdt0' ‘/var/public/SEMESTER/discrete/bdt0/Makefile’ -> ‘/home/USER/src/discrete/bdt0/Makefile’ ‘/var/public/SEMESTER/discrete/bdt0/bdt0.c’ -> ‘/home/USER/src/discrete/bdt0/bdt0.c’ ‘/var/public/SEMESTER/discrete/bdt0/check’ -> ‘/home/USER/src/discrete/bdt0/check’ ‘/var/public/SEMESTER/discrete/bdt0/in’ -> ‘/home/USER/src/discrete/bdt0/in’ ‘/var/public/SEMESTER/discrete/bdt0/in/data’ -> ‘/home/USER/src/discrete/bdt0/in/data’ ‘/var/public/SEMESTER/discrete/bdt0/in/sample0.txt’ -> ‘/home/USER/src/discrete/bdt0/in/sample0.txt’ make: Leaving directory '/var/public/SEMESTER/discrete/bdt0' lab46:~/src/discrete$

Experiencing xxd

If we don't know what it is we are implementing, we won't be all that successful. So, here's a quick overview of the xxd(1) tool we will be simulating aspects of; first up, a plain text look at a data file we will be processing:

lab46:~/src/discrete/bdt0$ cat in/sample0.txt >ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZ< [abcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz] 01: BINARY 01234567: OCTAL 0123456789: DECIMAL 0123456789ABCDEF:HEXADECIMAL )!@#$%^&*( . lab46:~/src/discrete/bdt0$

Note how it is filled with ASCII text- many of our recognizable symbols we use when using a text editor.

But, to illustrate how text is just a form of binary, witness what we are shown when we peel away a layer, and view the binary data (represented in hex for convenience) of that same file:

lab46:~/src/discrete/bdt0$ xxd in/sample0.txt 0000000: 3e41 4243 4445 4647 4849 4a4b 4c4d 4e4f >ABCDEFGHIJKLMNO 0000010: 5051 5253 5455 5657 5859 5a3c 0a5b 6162 PQRSTUVWXYZ<.[ab 0000020: 6364 6566 6768 696a 6b6c 6d6e 6f70 7172 cdefghijklmnopqr 0000030: 7374 7576 7778 797a 5d0a 3031 3a09 0920 stuvwxyz].01:.. 0000040: 4249 4e41 5259 0a30 3132 3334 3536 373a BINARY.01234567: 0000050: 0920 4f43 5441 4c0a 3031 3233 3435 3637 . OCTAL.01234567 0000060: 3839 3a09 2044 4543 494d 414c 0a30 3132 89:. DECIMAL.012 0000070: 3334 3536 3738 3941 4243 4445 463a 4845 3456789ABCDEF:HE 0000080: 5841 4445 4349 4d41 4c0a 2921 4023 2425 XADECIMAL.)!@#$% 0000090: 5e26 2a28 0a2e 0a ^&*(... lab46:~/src/discrete/bdt0$

The EXACT same file, with the EXACT same arrangement of data, only represented more as the computer looks at it (sequentially, one byte immediately following the next).

The output of xxd(1) has 3 distinct sections:

- the address or offset (from the start of file). This is a hexadecimal address, starting at 0 (beginning of the file), and increments according to the number of bytes displayed. You'll notice that there are (at maximum) the same number of bytes on each line, so the offset increments by that amount with each new line it displays.

- the actual data (represented in hex); here we see 8 columns of hex values, grouped together in pairs of two bytes (other hex viewers may separate into 16 columns, isolating each byte for better viewing).

- the ASCII rendering (far right field); if we are viewing an ASCII file, we will easily see the ASCII contents of this file. If we are viewing a non-ASCII file, we may still see random ASCII values, but that is just that the value stored in the particular byte maps to that ASCII value, and should NOT be considered actual ASCII data.

This is one of those conceptual roadblocks many develop- they think that binary is somehow more complicated than it is, and create all sorts of obstacles to effective access. Here we will try to break down some of those walls, because this is really important stuff to know.

Your task is to write a C program that takes a file name as a command-line argument, opens that file, reads its contents, and displays that data to the screen in the manner that the xxd(1) tool does in the above example (note that while the xxd(1) tool has other features, we are not looking to implement them; only this simple rendering view).

Your program must:

- Require the user supply a file via the command-line

- if the file specified does not exist/cannot be opened, display an error message and exit.

- error message should be of the form: Error: Could not open 'filename' for reading!

- Where filename is the name of the file specified on the command-line (make sure the quotes surround it in the output).

- no further processing should be done if the file is not able to be accessed.

- Detect the current size of the terminal (see “Detecting Terminal Size” section below), and record the lines and columns into variables for use in your program.

- If the terminal your program is being run in is less than 80 columns, display an error message and exit.

- error message should be of the form: Error: Terminal width is less than 80 columns!

- Your program will only be displaying to an area up to 80 characters wide, so a wider terminal will not influence program output.

- Similarly, if the number of lines in the terminal is less than 20, display a similar error message and exit.

- error message should be of the form: Error: Terminal height is less than 20 lines!

- Unlike the width, the height can impact program output (taller terminals, if not otherwise throttled by a second command-line argument, can auto-expand if there is more room and data to display).

- The second command-line argument is a sizing throttle (controlling the number of lines your program will display). If no argument, or a 0 is given, display the entire file.

- Each row will display:

- a 7-digit hex offset (referring to the first data byte on a given line)

- followed by a colon and a single space

- then eight space separated groups of two bytes

- however you arrive at it: two total spaces following the hex bytes (again, see output example)

- a 16-character ASCII representation field (no separating spaces between the values)

- all printable characters should be displayed.

- all non-printable (and various whitespace) characters should be substituted with a '.'

- A newline will be the last character on each line.

- The hex values and rendered ASCII displayed will be sourced from the file specified on the command-line. While the target files for this project are less than 512 bytes, your program should be able to handle larger and smaller files, and update its display accordingly.

- If a line throttle is given, your program is to stop output of data and ASCII rendering at that line, once it completes.

- Once the data in the file has been exhausted, you need to wrap up as appropriate; finish the current line (even if you have to pad spaces), display the corresponding ascii field (padding spaces as appropriate).

- Don't forget to fclose() any open file pointers! And free() any malloc()'ed or calloc()'ed memory.

- If provided (via command-line arguments), highlight the offset field and the specified address + length (see below).

- If the last pair is not complete (ie only an address given), ignore that request.

Detecting Terminal Size

To detect the current size of your terminal, you may make use of the following code, provided in the form of a complete program for you to test, and then adapt into your code as appropriate.

It makes use of a pre-existing structure, which when properly populated with an ioctl() call, you have the information you need to proceed (we're just using it to retrieve information to help us on our program).

#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <sys/ioctl.h> int main (void) { struct winsize terminal; ioctl (0, TIOCGWINSZ, &terminal); printf ("lines: %d\n", terminal.ws_row); printf ("columns: %d\n", terminal.ws_col); return (0); }

An ioctl(2) is a method (and system/library call) for manipulating underlying device parameters of special files (for the UNIX people: everything is a file, including your keyboard, and terminal screen). We are basically querying the screen (or accessing lower level information made possible by communicating with the driver of the device) to obtain some useful information. If you've ever wondered how drivers work- this ioctl() functionality can be rather central to the whole process (basically, reading or writing bytes at specific memory addresses).

Here we are accessing the information on our terminal file, retrieving the width and height so that we can make use of them productively in our programs.

Compile and run the above code to see how it works. Try it in different size terminals. Then incorporate the logic into your hex viewer for this project.

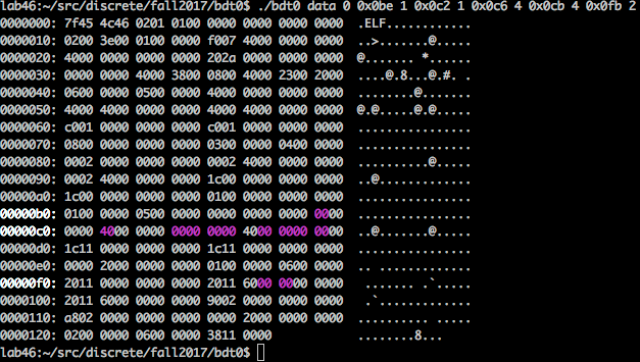

Selection highlighting

The following adds a nice visual twist to things:

- Enhance the program to accept pairs of additional values (offset followed by its length), where each offset through length will be colored using ANSI text escape sequences (for simplicity, you may highlight using the same color).

- For any line containing this colorized text, highlight the address in bold white.

Sample output

ANSI escape sequences for color

This probably isn't very portable, and depending on the terminal, it may not work for some people.

It may be most convenient to set up preprocessor #define statements near the top of your code, as follows:

#define ANSI_RESET "\x1b[0m" #define ANSI_BOLD "\x1b[1m" #define ANSI_FG_BLACK "\x1b[30m" #define ANSI_FG_RED "\x1b[31m" #define ANSI_FG_GREEN "\x1b[32m" #define ANSI_FG_YELLOW "\x1b[33m" #define ANSI_FG_BLUE "\x1b[34m" #define ANSI_FG_MAGENTA "\x1b[35m" #define ANSI_FG_CYAN "\x1b[36m" #define ANSI_FG_WHITE "\x1b[37m" #define ANSI_BG_BLACK "\x1b[40m" #define ANSI_BG_RED "\x1b[41m" #define ANSI_BG_GREEN "\x1b[42m" #define ANSI_BG_YELLOW "\x1b[43m" #define ANSI_BG_BLUE "\x1b[44m" #define ANSI_BG_MAGENTA "\x1b[45m" #define ANSI_BG_CYAN "\x1b[46m" #define ANSI_BG_WHITE "\x1b[47m"

To use, you output them:

fprintf(stdout, ANSI_FG_GREEN); fprintf(stdout, "This text is green\n"); fprintf(stdout, ANSI_RESET);

You have to remember to turn the color or setting off (resetting it) to revert back to the original color.

You can mix and match as well:

fprintf(stdout, ANSI_FG_YELLOW); fprintf(stdout, ANSI_BG_BLUE); fprintf(stdout, ANSI_BOLD); fprintf(stdout, "This text is bold yellow on blue\n"); fprintf(stdout, ANSI_RESET);

While there are 8 available foreground colors, bolding can double that range to 16.

Verification

I'm working on an eval script that should aid you in verifying how compliant your implementation is against project specifications.

make check

I've tied in the running of the verification script into the Makefile. To utilize it, all you have to do is type “make check” and follow any on-screen prompts.

It may stop to prompt you after completing each category of tests so that you can better analyze the results (or hit CTRL-c to exit out of the script and address any issues).

For example, let's say there's a problem with the first file:

lab46:~/src/discrete/bdt0$ make check =================================== = discrete/bdt0 Evaluation Script = =================================== [Part 0]: Compliance with xxd output ... ----[ audio.mp3 ]--------------------------------------------------- xxd: 17152 char, 256 lines, md5: 57bd8a3badfef2a39cd7bccd7f86c03d bdt0: 17194 char, 257 lines, md5: 63376e4205135c2d0e520884a6e861ff ---------------------------------------------------------------------- CHK: MISMATCH MISMATCH MISMATCH ---------------------------------------------------------------------- ----[ data ]--------------------------------------------------- xxd: 1269 char, 19 lines, md5: 1a9bab04b8ebdb523c1d3e722845a6c5 bdt0: 1269 char, 19 lines, md5: 1a9bab04b8ebdb523c1d3e722845a6c5 ---------------------------------------------------------------------- CHK: OK OK OK ---------------------------------------------------------------------- ----[ s13.p.rle ]--------------------------------------------------- xxd: 6564 char, 98 lines, md5: 24895128bce7a041f553226c7981c0d4 bdt0: 6564 char, 98 lines, md5: 24895128bce7a041f553226c7981c0d4 ---------------------------------------------------------------------- CHK: OK OK OK ---------------------------------------------------------------------- ----[ sample0.txt ]--------------------------------------------------- xxd: 661 char, 10 lines, md5: 4e01dda9d62c98781664f9fed8d494ff bdt0: 661 char, 10 lines, md5: 4e01dda9d62c98781664f9fed8d494ff ---------------------------------------------------------------------- CHK: OK OK OK ---------------------------------------------------------------------- Tally: 9/12 | Press ENTER to continue lab46:~/src/discrete/bdt0$

With the individual char and line counts, we can get some impression of things being off in more significant ways (and of course the MD5sums will not match).

You can then run things manually to see the end results.

Implementation Restrictions

As our goal is not only to explore the more subtle concepts of computing but to promote different methods of thinking (and arriving at solutions seemingly in different ways), one of the themes I have been harping on is the stricter adherence to the structured programming philosophy. It isn't just good enough to be able to crank out a solution if you remain blind to the many nuances of the tools we are using, so we will at times be going out of our way to emphasize focus on certain areas that may see less exposure (or avoidance due to it being less familiar).

As such, the following implementation restrictions are also in place:

- absolutely NO switch/case, continue, break, nor other non-structured program flow alteration (jumps, gotos, etc.)

- absolutely NO infinite loops (while(1), which are more-or-less unviable anyway if you cannot break out of them).

- no forced redirection of the flow of the process (no seeking to the end of the file to grab a max size only to zip back somewhere else: deal with the data in as you are naturally encountering it).

- With the exception of any negative values, all numbers should be transacted in hexadecimal (as in the values you assign and compare and manipulate in your code).

- No line must exceed 80 characters in width.

- All “arrays” must be declared and referenced using ONLY pointer notation, NO square brackets.

- For the highlighted address and lengths, store them in an array of structs (containing the address and length members).

- NO logic shunts (ie having an if statement nested inside a loop to bypass an undesirable iteration)- this should be handled by the loop condition!

Submission

To successfully complete this project, the following criteria must be met:

- Code must compile cleanly (no warnings or errors)

- Use the -Wall and –std=c99 flags when compiling (which occurs automatically when using make).

- Code must be nicely and consistently indented (you may use the indent tool)

- Code must utilize the algorithm/approach presented above

- Implementation must be free from stated restrictions above

- Output must match the specifications presented above (when given the same inputs)

- Code must be commented

- be sure your comments reflect the how and why of what you are doing, not merely the what.

- Track/version the source code in a repository

- Submit a copy of your source code to me by running make submit

To submit this program to me using the Makefile tool (make submit), run the following:

lab46:~/src/discrete/bdt0$ make submit removed ‘bdt0’ removed ‘errors’ Project backup process commencing Taking snapshot of current project (bdt0) ... OK Compressing snapshot of bdt0 project archive ... OK Setting secure permissions on bdt0 archive ... OK Project backup process complete Submitting discrete project "bdt0": -> ../bdt0-20170925-05.tar.gz(OK) SUCCESSFULLY SUBMITTED lab46:~/src/discrete/bdt0$

You should get some sort of confirmation indicating successful submission if all went according to plan. If not, check for typos and or locational mismatches.